By Terry Ann Gordon | June 26, 2023

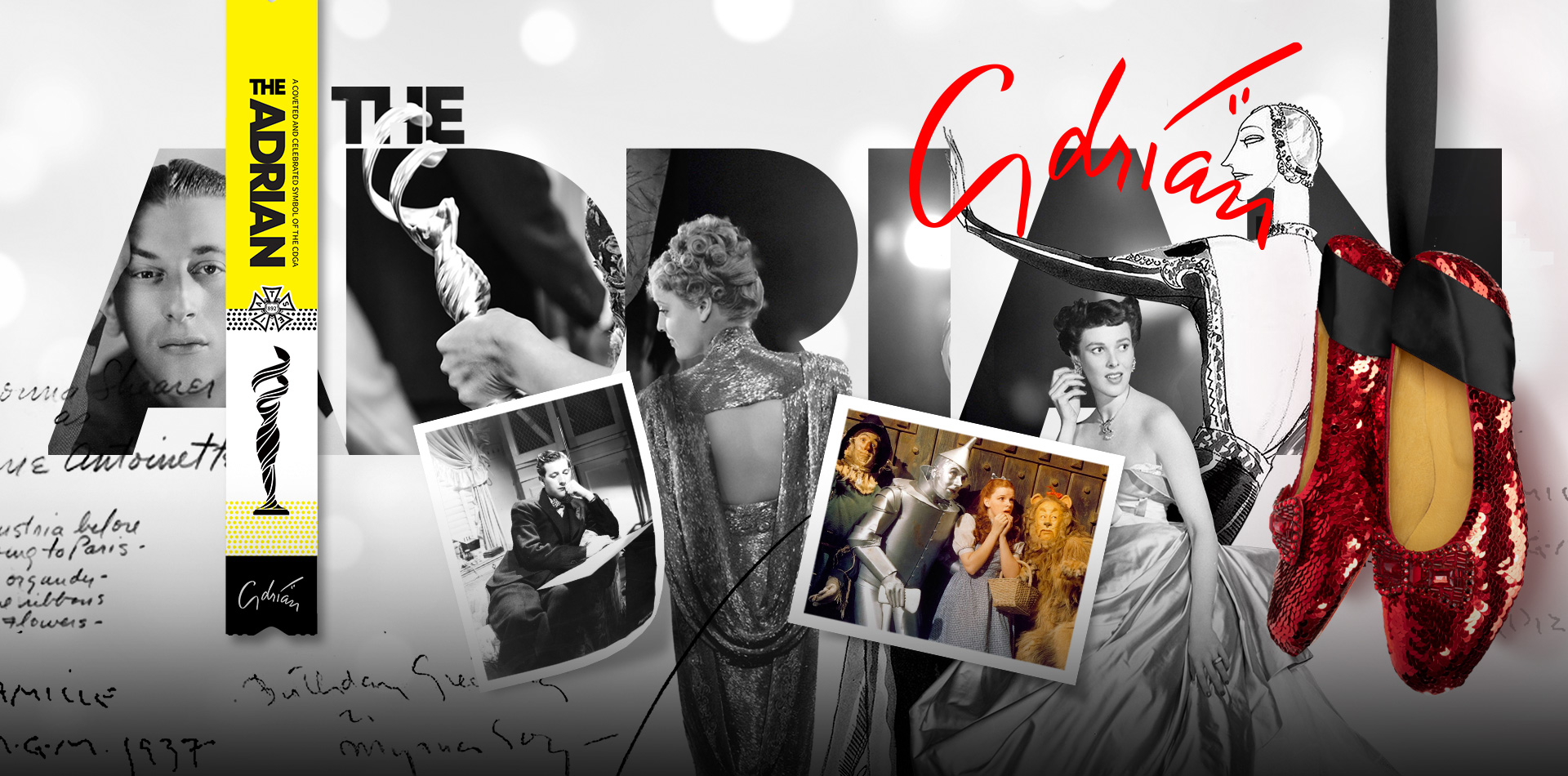

The Adrian

Celebrating our 25th CDGA was a beautiful collage of our past, present, and future. Honoring our history by officially christening our Awards statuette remains my most memorable and cherished moment. Film has the Oscar, television has the Emmy, and now—we have the Adrian.

In 1953 nine Hollywood costume designers—Marjorie Best, Renié Conley, Elois Jenssen, Sheila O’Brien, Leah Rhodes, Howard Shoup, William Travilla, Michael Woulfe, and Charles LaMaire—came together to form the Costume Designers Guild “to advance the economic, professional and cultural interests of its members.” At that time they also created our designers “stamp.” Used on costume illustrations and documents, all stamps are numbered to indicate that member’s Guild installation. Though never an official member, the iconic and prolific costume designer’s influence is evident, as Adrian was awarded the first stamp.

Following years of ongoing Executive Board discussions, we reached out to Gilbert Adrian’s son, Robin Gaynor Adrian, who granted the CDG permission to use Adrian’s name for our award. Appreciative of this honor, Robin says, “My father would be thrilled to know he’s remembered with this elegant tribute made in his name.”

Designed by costume designer David LeVey and originally minted by the jeweler Bvlgari, our statuette embodies timeless glamour, elegance, and energy. LeVey’s design was inspired by the Golden Age of Hollywood and the 1951 film Singin’ in the Rain’s “Broadway Melody Ballet” designed by Walter Plunkett. As Cyd Charisse and Gene Kelly dance across a surreal vacant stage, the drama of the scene is showcased, driven, and emphasized by the costume. Designing dramatic and powerful female silhouettes was Adrian’s forte and is embodied in our statuette.

Born Adrian Adolph Greenburg on March 3, 1903, in Naugatuck, Connecticut, his creative parents embraced the arts and encouraged Adrian to draw. His mother taught him color theory and their housekeeper taught him to sew. His devotion to art, love of animal sketching and all that was exotic led to his enrolling in what is now Parsons New York. Early in his career he signed his work Gilbert Adrian. Advised to change his signature, he became the singular—Adrian.

At 19, Adrian left Parsons to continue his studies in Paris. Encouraged to attend the extravagant annual Bal du Grand Prix to showcase his talent, Adrian created his date’s elaborate costume. Fellow attendee Irving Berlin’s “fixed gaze” on Adrian’s date assured that his design was a success. Berlin immediately invited Adrian to return to New York to design his Broadway show, Music Box Review (1922-23). His costume and set designs for the review catapulted him into the upper echelon of New York’s theater community for the next two years.

In 1924, Rudolph Valentino’s designer/manager/wife, Natacha Rambova, spied Adrian’s portfolio and lured him away from Broadway to design their films in Hollywood. Collaborating with the Valentinos on their films, a flurry of job offers followed from industry notables of the era. Adrian chose DeMille, whose dramatic flair, love of color and texture offered him the forum to translate his designs into flights of fancy. Over a two-year period, Adrian designed two dozen films with DeMille. When DeMille’s studio failed in its third year, they both moved to MGM.

Aware of his MGM stars’ magnified personalities, Adrian wrote: “I found that meeting with a star was like conducting a session in psychoanalysis. To create my designs, I had to see the direction of her drive. I studied her, deciding how I would fire her imagination. To watch the unfurling of each woman’s emotions was part of my job.”

Designing over 250 films between 1928-41 for MGM at the height of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Adrian became renowned for his design versatility. Period, contemporary, and fantasy features were met with equal ability and artistry. His extravagant panniers for Norma Shearer’s Marie Antoinette (1938), as well as Jean Harlow’s exquisite bias-cut gowns for Dinner at Eight (1933) showcased the breadth of his abilities. Considered “the height of forward-thinking style,” Adrian designed Joan Crawford’s organdy evening gown in Letty Lynton (1932). His impact reverberated throughout culture and global fashion.

1939 brought two legendary films. In The Women, Adrian deftly expressed a range of female personalities through costume, and The Wizard of Oz changed cinema forever. In Leonard Stanley’s book Adrian, Adrian’s son Robin recalled, “…it was the film he loved the most, because it allowed him to do … some pretty outlandish things. He really loved animals, so putting together the look of the flying monkeys was a real highlight for him.” He adds, “I was always so impressed by how my father could multitask. He would be sitting at his desk working on a sketch, approving a fitting that was happening a few feet away, and talking on the phone all at the same time. He was an incredible talent.” Adrian left MGM in 1941, refusing an order to make Garbo “more like a typical American girl.” He famously stated, “When the glamour ends for Garbo, it also ends for me.”

Adrian retired from Hollywood prior to Oscars being awarded for costume design in 1949 to continue designing his namesake clothing line and theater. He passed away in 1959. Robin says, “My only disappointment is that he never received an Oscar. When you think about my father’s work, he should have gotten seven or eight of them.”

The Costume Designers Guild is honored to name our awards statuette “the Adrian” in honor of Gilbert Adrian’s lasting contributions to the art of costume design.